Why is it Called That? Decoding the Secret History of British Pub Signs

Walk down any high street in Britain, from the cobbles of York to the winding lanes of a Cornish fishing village, and you are walking through an open-air art gallery.

It hangs above your head, creaking in the wind on wrought-iron brackets: The Red Lion, The White Hart, The Royal Oak.

For most of us, these names are just waypoints—a place to meet for a Sunday roast or a pint of ale after a long hike.

But if you stop to look up, you aren’t just seeing a name; you are reading a code that has been used for two thousand years.

In an era when few could read, these painted boards were the “social media” of their day, broadcasting political loyalty, religious affiliation, and even the local blood sports.

Here is how to decode the secret history hanging above the door.

The Roman Bush: Where it All Began

The British pub sign didn’t start with paint; it started with a plant. When the Romans arrived in Britain, they brought their tabernae (wine shops) with them.

In Rome, a vine leaf hung outside the door signalled that wine was sold within.

However, Britain’s climate was hardly conducive to growing vines, so the Romans adapted, hanging bundles of evergreen bushes outside their alehouses instead.

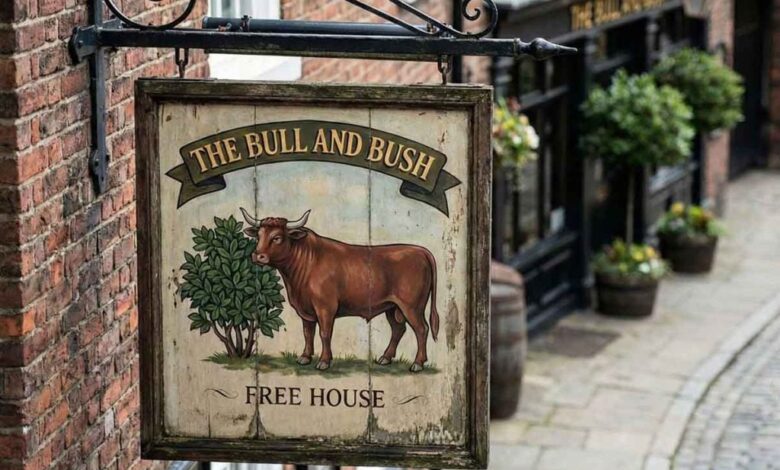

This ancient substitution survives today. If you have ever visited a pub called The Hollybush or The Bull and Bush, you are looking at a direct linguistic fossil of the Roman occupation.

The White Hart: The King’s Badge

By the 14th century, alehouses were so common that regulation was needed. In 1393, King Richard II passed an act making it compulsory for pubs to display a sign so that the official “ale conners” (tasters) could identify them and check the quality of the brew.

Many landlords, eager to show loyalty to the volatile King, adopted his personal badge: The White Hart.

This explains why, over 600 years later, the White Hart remains one of the most common pub names in the country. It wasn’t just a name; it was a medieval political bumper sticker saying, “We support the King.”

The Red Lion and the Royal Oak: A Game of Thrones

If you travel the country, you will inevitably end up in a Red Lion; it is the most common pub name in Britain.

While some claim it represents John of Gaunt, it most widely symbolises King James I (VI of Scotland), who ordered the red lion of Scotland to be displayed on public buildings upon his accession to the English throne in 1603.

Similarly, The Royal Oak is a specific nod to the future Charles II. During the English Civil War in 1651, the young prince hid in an oak tree at Boscobel House to escape the Roundheads after his defeat at the Battle of Worcester.

When the monarchy was restored in 1660, pubs across the land renamed themselves The Royal Oak to celebrate the King’s survival. It was a clear signal to your neighbours: “We are Royalists here.”

Conversely, The Rose and Crown celebrates the end of the War of the Roses, symbolising the union of the warring houses of York and Lancaster under the Tudors.

The Reformation Rebrand: Hiding in Plain Sight

Perhaps the most fascinating layer of pub history comes from the Reformation, when Henry VIII split from the Catholic Church.

Suddenly, having a pub with a Catholic name was dangerous. Landlords had to rebrand quickly to avoid being branded as heretics.

The Ark became The Ship.

St. Peter (the keeper of the keys to heaven) became The Cross Keys. If you visit The Cross Keys in Nottingham’s Lace Market, you are visiting a site that carries this coded religious history.

The Salutation (referring to the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary) was often secularised to The Soldier or simply The Angel.

The Darker Side: Bears and Hangmen

Not all signs were about loyalty; some were advertisements for entertainment, and often grisly ones.

Pubs named The Dog and Bear or The Bear are frequently located near historic bear-baiting pits. The sign let illiterate locals know that they could watch “sport” along with their ale.

Even more macabre is The Strugglers. While it sounds like a sympathetic nod to the working class, these pubs were often situated near public execution sites.

The “struggle” referred to the grim dance of the hanged man. Famously, the executioner Albert Pierrepoint was the landlord of a pub called Help The Poor Struggler.

Reading the Streets

Next time you are on a hike and spot a swinging sign, take a moment to decode it.

Is it a White Horse (signalling the Hanoverian kings)? Is it The Gate (often signaling the limit of the sheriff’s jurisdiction)?

These signs are more than just decoration; they are the illustrated history of Britain, telling us stories of kings, wars, religion, and daily life that have survived for centuries, hanging right above our heads.

Source link