Webb Reveals Pristine Star Clusters in an Early Universe Galaxy – World Pakistan

The Cosmic Gems arc as observed by the JWST. Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, L. Bradley (STScI), A. Adamo (Stockholm University) and the Cosmic Spring collaboration.

The history of how stars and galaxies came to be and evolved into the present day remains among the most challenging astrophysical questions to solve yet, but new research brings us closer to understanding it.

A recent international study led by Dr. Angela Adamo at Stockholm University has unveiled fresh insights into young galaxies from the Epoch of Reionization. Utilizing the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), researchers studied the Cosmic Gems arc galaxy (SPT0615-JD), confirming that its light originated 460 million years after the Big Bang. What makes this galaxy unique is that it is magnified through an effect called gravitational lensing, which has not been observed in other galaxies formed during that age. The magnification of the Cosmic Gems arc has allowed the team to study the smaller structures inside an infant galaxy for the first time.

The researchers discovered that the Cosmic Gems arc harbors five young massive star clusters in which stars are formed. “The surprise and astonishment were incredible when we opened the JWST images for the first time,” says Adamo.

The Mystery of the Early Universe

The Epoch of Reionization (EoR) is a crucial time during the evolution of the Universe, which occurred within the first billion years after the Big Bang. During this period, the Universe went through an important transition. In its early days it was filled with neutral Hydrogen gas, but this changed during the EoR. The matter of the Universe went from its neutral form to being fully ionized; the atoms were stripped of their electrons. The earliest galaxies of the Universe are believed to have driven this transformation.

In order to study the earliest galaxies one has to look far away in space. Light travels at a finite speed. By observing objects at far distances we can “look back in time” as we see the state of the object at the time when the light was emitted from it. However, it is difficult to observe small details of an object at large enough distances to study the early Universe.

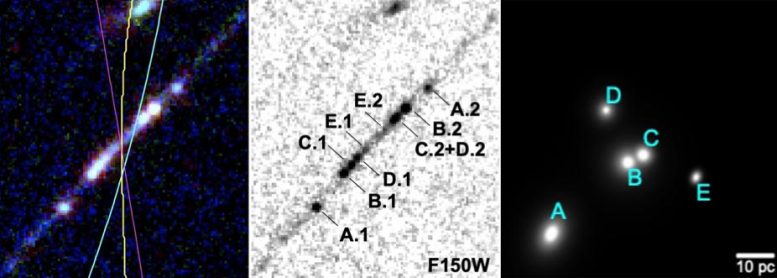

A zoom-in on the mirrored star clusters in the Cosmic Gems arc. Middle: a negative version of the star clusters, where the different star clusters are marked. Right: the star clusters “behind” the gravitational lens. This image was calculated using computer simulations. Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, L. Bradley (STScI), A. Adamo (Stockholm University) and the Cosmic Spring collaboration

One method to observe finer details in a galaxy at a great distance is through the use of gravitational lensing. Gravitational lensing occurs when a celestial body of high mass curves the path of light around it due to its strong gravity. When the light emitted from a source passes through the gravitational lens it is distorted similar to the effect of a magnifying glass. In this way, astronomers can observe small details in objects far away.

Galaxies slowly build their stellar population through a process referred to as star formation. In local galaxies we see that a large fraction of stars form in star clusters. Star clusters are groups of stars held together by gravitational forces. Star clusters can have varying sizes, where some only contain a small number of stars to others that can contain millions. Globular clusters are very old star clusters where stars have previously been formed, but not anymore. How and where the globular clusters were formed has been a long-standing mystery.

Advanced Observations with JWST

In a new study published in the scientific journal Nature, the team of astronomers present the discovery of star clusters in a galaxy whose light has passed through a gravitational lens on its way toward the Earth. “This achievement could only be possible thanks to JWST unmatched capabilities,” says Dr. Adélaïde Claeyssens of Stockholm University and co-author of the publication. The galaxy SPT0615-JD, also known as the Cosmic Gems Arc, is located in the distant Universe. The light that has reached the Earth in the present day was emitted from this galaxy only 460 million years after the Big Bang. By studying this object, the astronomers look back 97% of the cosmic time.

The Power of NIRCam and Star Cluster Discovery

“Due to the gravitational lensing, the Cosmic Gems Arc could be resolved down to small enough scales to study the objects within it,” adds Claeyssens.

The team used the Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) instrument onboard the JWST for their observations. The NIRCam is built to take high-resolution images in the near-infrared part of the light spectrum, in which the earliest stars and galaxies can be detected. Using the high resolution of the JWST NIRCam, the resulting observations showed a chain of bright dots mirrored from one side to the other. It was discovered that these dots were five young massive star clusters.

The Significance of Discovering Early Star Clusters

Through analysis of the light spectra emitted by the galaxy, it could be determined that the stellar clusters are gravitationally bound and have a three-times larger stellar density than typical young star clusters in the local Universe. It was also found that the clusters were formed recently, within 50 million years. They are very massive, although much smaller than globular clusters.

“It was incredible to see the JWST images of the Cosmic Gems arc and realize that we were looking at star clusters in such a young galaxy. We observe globular clusters around local galaxies, but we don’t know when and where they formed. The Cosmic Gems arc observations have opened a unique window for us into the works of infant galaxies as well as showing us where globular clusters formed,” says Adamo. “These clusters will have enough time to relax and become globular clusters, due to them being formed at such a young age of the Universe,” she adds.

Understanding the Early Universe

Through studies of star clusters in young galaxies born shortly after the Big Bang, further understanding of how and where globular clusters are formed can be achieved. Since young galaxies are believed to drive the reionization during the EoR, it is crucial to study them in depth in order to gain knowledge about the early Universe. Using the discoveries made by the authors of this study, more information is added to our understanding of how the stars in the earliest galaxies were born, and where and how globular clusters are formed.

Looking Onwards

In the future, the group is planning to build a larger sample of similar galaxies. “We have one galaxy so far, but we need many more if we want to create demographics of the cluster populations forming in the earliest galaxies,” says Adamo.

The team also has an approved program for the next cycle of JWST observations, where they will study the Cosmic Gems Arc galaxy and the recently discovered star clusters in further detail. “Spectroscopic observations will allow us to spatially map the star formation rate and ionizing photon production efficiency along the galaxy” adds Dr. Larry Bradley, principal investigator of the JWST program and the second author of this article.

Reference: “Bound star clusters observed in a lensed galaxy 460 Myr after the Big Bang” by Angela Adamo, Larry D. Bradley, Eros Vanzella, Adélaïde Claeyssens, Brian Welch, Jose M. Diego, Guillaume Mahler, Masamune Oguri, Keren Sharon, Abdurro’uf, Tiger Yu-Yang Hsiao, Xinfeng Xu, Matteo Messa, Augusto E. Lassen, Erik Zackrisson, Gabriel Brammer, Dan Coe, Vasily Kokorev, Massimo Ricotti, Adi Zitrin, Seiji Fujimoto, Akio K. Inoue, Tom Resseguier, Jane R. Rigby, Yolanda Jiménez-Teja, Rogier A. Windhorst, Takuya Hashimoto and Yoichi Tamura, 24 June 2024, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07703-7

Dr. Angela Adamo, Associate Professor of the Galaxy group at the Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University, is the lead author of the article. Dr. Adélaïde Claeyssens is a Postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University, and Erik Zackrisson, Associate Professor at the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Uppsala University, are co-authors of the study.