Universal Equation Links Wingbeats of Whales to Mosquitoes

Danish researchers developed a universal equation that predicts the wingbeat and fin stroke frequencies of various animals using body mass and wing area. Credit: SciTechDaily.com

Researchers from Roskilde University in Denmark have developed a universal equation that can effectively predict the frequency of wingbeats and fin strokes made by birds, insects, bats, and whales. This groundbreaking research was recently published in the journal PLOS ONE.

The capability of flight has evolved independently across different animal groups. Biologists have theorized that to minimize energy expenditure during flight, the natural resonance frequency of the wings should dictate the wing flapping frequency. However, finding a universal mathematical description of flapping flight has proved difficult.

In their study, the researchers used dimensional analysis to calculate an equation that describes the frequency of wingbeats of flying birds, insects, and bats, and the fin strokes of diving animals, including penguins and whales.

Empirical Validation of the Universal Equation

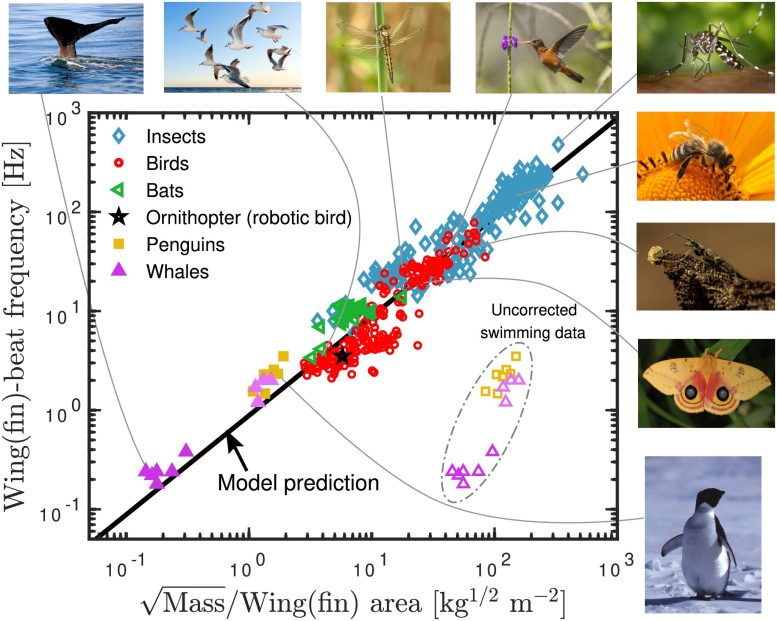

The researchers found that flying and diving animals beat their wings or fins at a frequency that is proportional to the square root of their body mass, divided by their wing area. They tested the accuracy of the equation by plotting its predictions against published data on wingbeat frequencies for bees, moths, dragonflies, beetles, mosquitos, bats, and birds ranging in size from hummingbirds to swans.

Wing-beat-frequency data for a variety of flying animals versus the square-root of the animal mass divided by the wing/fin area. Credit: Jensen et al., 2024, PLOS ONE, CC-BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Cross-Species Comparison and Historical Insight

They also compared the equation’s predictions against published data on fin stroke frequencies for penguins and several species of whale, including humpbacks and northern bottlenose whales. The relationship between body mass, wing area, and wingbeat frequency shows little variation across flying and diving animals, despite huge differences in their body size, wing shape, and evolutionary history.

Additionally, the researchers demonstrated how their equation could provide insights into the wingbeat frequency of extinct species. Using their equation, the researchers estimated that the extinct pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus northropi, the largest known flying animal, beat its 10-meter-square wings at a frequency of 0.7 hertz.

Implications for Biology and Future Technologies

The study shows that despite huge physical differences, animals as distinct as butterflies and bats have evolved a relatively constant relationship between body mass, wing area, and wingbeat frequency. The researchers note that for swimming animals they didn’t find publications with all the required information; data from different publications was pieced together to make comparisons, and in some cases, animal density was estimated based on other information. Furthermore, extremely small animals — smaller than any yet discovered — would likely not fit the equation, because the physics of fluid dynamics changes at such a small scale. This could have implications in the future for flying nanobots. The authors say that the equation is the simplest mathematical explanation that accurately describes wingbeats and fin strokes across the animal kingdom.

The authors add: “Differing almost a factor 10000 in wing/fin-beat frequency, data for 414 animals from the blue whale to mosquitoes fall on the same line. As physicists, we were surprised to see how well our simple prediction of the wing-beat formula works for such a diverse collection of animals.”

Reference: “Universal wing- and fin-beat frequency scaling” by Jens Højgaard Jensen, Jeppe C. Dyre and Tina Hecksher, 5 June 2024, PLOS ONE.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0303834

Funding: This study was supported by the VILLUM Foundation’s Matter grant VIL16515.