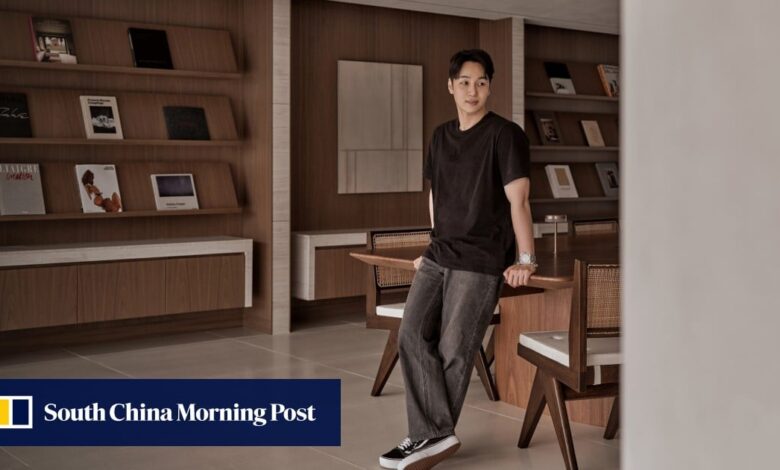

Seoul-based furniture brand Eastern Edition’s Teo Yang on sustainability and minimalism in Korean culture, and making ‘the old aesthetic into an international language’

“Another question that came up for us was cultural sustainability,” Yang says of his thought process when building the brand, which now has four showrooms across Seoul, Paris and Los Angeles. “How do we sustain our culture? How do we make sure that these old, beautiful narratives don’t just stay in the books, but can still inspire people in the 21st century?”

Asking these sorts of questions helped Yang become a household name over the years, making his mark as a triple-threat designer, entrepreneur and creative visionary. Before launching Eastern Edition, he was already the founder of his own eponymous design studio, and even co-founded a skincare line, EATH Library, inspired by the same principles. He’s been tapped by luxury brands like Chanel, with whom he curated an exhibition supporting traditional Korean crafts, and more recently designed a new outlet of Blue Bottle, the popular coffee chain, in the heart of Seoul’s busy Myeongdong district.

Years of working on massive client projects have taught him a thing or two about balancing traditional desires with contemporary needs. One thing you’ll notice right away about Eastern Edition furniture is that though the aesthetics remain universally palpable in their design essentials – clean lines, simple shapes – its distinctly Asian sensibility is what gives the brand its unique charm. “We always try to make the old aesthetic into an international language because we want to speak to everyone,” says Yang.

Bringing a traditional way of living into the 21st century – to connect past and present through design philosophy – is a unique element that separates Eastern Edition from its contemporaries, giving new meaning to the phrase “lifestyle brand”. While minimalist in appearance, the brand’s furniture is designed to add something to your life: it doesn’t just make you feel at home, but prompts you to think about what home actually means. Translating that to a modern-day audience remains Yang’s biggest challenge. “We don’t necessarily need to follow trends, but we need to adapt the contemporary aesthetic in order to convey [our] message across to clients.”

That message, as he explains, is indispensable in a design scene otherwise dominated by Western brands. “It’s very important that we offer diversity … It’s really hard to find a furniture brand that has founders with Asian designers, basically. Of course, there’s Neri & Hu, and also André Fu, which is great. It’s basically like the ecosystem – if there’s only one species taking over, it’s a very unhealthy environment. But having all these different, diverse brands come together – we compete, we learn from each other, we collaborate.”

“We always question, if the modernisation was not handled by the West – if we took on our own modernisation – what would it look like?” Yang asks. He explains that Eastern Edition’s philosophy is further informed by how cultural traditions have evolved over time. “Another thing people think, especially Asians – I’ve seen this with a lot of Japanese, Chinese and Korean people – they think they know their own culture and heritage, but we don’t. Lifestyle-wise, we don’t wear traditional clothing. We don’t use traditional furniture any more. We live in such a new state, in such a Western way.”

Yang points to the brand’s cushion stool as an example. “In the old days, we would sit on the floor, sleep on the floor, and [a] cushion was a symbol of hospitality.” Eastern Edition’s version balances two sleek, simple pillows atop a modest wooden structure, demonstrating how the brand bridges the cultural and generational gap by bringing traditional sensibilities to modern lifestyles. It’s not necessarily designed to impress, but rather to invoke a sense of belonging. “Even my grandma would tell me, if she didn’t like someone, she would never offer them a cushion,” he laughs.

![“If [my grandma] didn’t like someone, she would never offer them a cushion,” Teo Yang says](https://img.i-scmp.com/cdn-cgi/image/fit=contain,width=1024,format=auto/sites/default/files/d8/images/canvas/2024/07/30/a90a07bd-a50b-4099-8731-df5385ffc814_298b643e.jpg)

Indeed, long before minimalism became trendy, Yang says his ancestors were already rejecting the ostentatious. “There’s this one quote in Korea which became a standard for Korean aesthetics. Create something that’s down to earth, but it shouldn’t be too humble – and create something beautiful, but it shouldn’t be extravagant. That was even the guideline for the building of the first palace in the Joseon Dynasty.”

Even then, it’s not as easy as simply copying and pasting traditions into something more palatable for modern audiences. “We’re not just trying to borrow the aesthetic of simpleness,” he clarifies. “We’re trying to talk about the essence and the philosophy of ‘simple’. What is simple? Simple is eliminating and abandoning all the decorativeness … It’s about looking at the essence of things, and really digging into the core message [of what] we’re doing. It’s about going deep into yourself, thinking about yourself and enhancing yourself.”

And isn’t striving for a simpler lifestyle key to living a happy life? Ultimately, Eastern Edition’s purpose is to prove that living well starts with good design. “Our staff in our studio, they always say, ‘Oh, we’re not designers. We’re people who study humans,’” says Yang. “When we get projects, we always think, what are the problems? How can we solve them? It’s really about growing together as a designer, as a brand, with the customer. That’s what makes it worthwhile.”

This design-first approach to living is how traditions endure through Eastern Edition furniture, which makes the past relevant by bringing the past to life. The brand’s latest Persimmon Tree collection, now available at Lane Crawford, draws on a historically cherished part of traditional Korean scenery by using the persimmon tree as material for its beautiful colour and texture – what Yang calls “the next Brazilian rosewood”. He also gives materials from demolished 18th-century housing a second life in the brand’s new column floor lamp.

Rather than pining for the finer, fancier things in life, Yang posits that Eastern Edition is an invitation to turn inward and develop a deeper appreciation for our surroundings through the celebration of heritage – both what’s left of it and what’s yet to come. “One of the jobs I think I’m doing is creating an archive, measuring possibilities of creation,” says Yang. “As a Korean designer living in Seoul, working in the 21st century, I constantly challenge myself: what can I offer to the world?”

Source link