Groundwater Depletion Maps Reveal Depths of “Extreme” and “Exceptional” Mexican Drought

Satellite view of water in Valle de Bravo reservoir in Mexico captured on May 20, 2022, by the OLI on Landsat 8.

Satellite view of water in Valle de Bravo reservoir in Mexico captured onMay 17, 2024, by the OLI-2 on Landsat 9.

Mexico’s severe drought since 2023 has led to critical water shortages, especially in Mexico City, with drastically lowered reservoir and groundwater levels, though seasonal rains may offer some relief.

Beginning in the summer of 2023, one of the most severe droughts that Mexico has faced in more than a decade began to bake the North American country. Over the following year, the drought intensified and spread widely.

“Extreme” and “exceptional” drought, as classified by the North American Drought Monitor, now afflicts several states in Mexico. States experiencing these categories of drought include Sonora, Chihuahua, Sinaloa, and Durango in northern Mexico, as well as Tamaulipas, San Luis Potosí, Guanajuato, Querétaro, and Hidalgo farther south.

Impact on Water Systems and Agriculture

As the drought persists, it is parching crops, exacerbating fires, and straining water systems throughout the country. Concerns about water supplies have become particularly acute in Mexico City, the capital city of 19 million people, where reservoirs have dipped to historically low levels and groundwater aquifers are nearly depleted.

The images above, acquired by the OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat 8 and OLI-2 on Landsat 9, show water in Valle de Bravo, one of three major reservoirs that store water for Mexico City. The reservoir is part of the Cutzamala water system, an inter-basin network of reservoirs and canals that conveys surface water from the Cutzamala River to Mexico City. It provides the city with about 25 percent of its water. A second water network that connects to the Lerma River provides about 8 percent of the city’s water. The rest comes from wells that tap into groundwater aquifers.

Crisis in Water Levels and Reservoir Capacity

The lower image above shows the reservoir on May 17, 2024, the clearest recent day to coincide with a Landsat overpass. Mexico’s Water Department, Conagua, reported that water levels in the reservoir had dropped to 28 percent of capacity on June 7, 2024. The top image shows the reservoir on May 20, 2022, when the Cutzamala system contained about twice as much water. The amount of water in the Cutzamala system overall has dropped to roughly 25 percent of total capacity. The lack of water has prompted officials to start reducing the amount of water the system delivers to Mexico City, and some analysts warn that many taps in the city could run dry in the coming months.

The amount of annual precipitation in the Cutzamala basin in 2022 and 2023 was about one-third of the average for the past 40 years, according to meteorological data. This lack of rain and surface water, and a potent heat wave in May that increased the rate of evaporation from surface water, have intensified the need for groundwater pumping in recent months, contributing to the parched state of aquifers in the region.

Monitoring Groundwater and Seasonal Relief Outlook

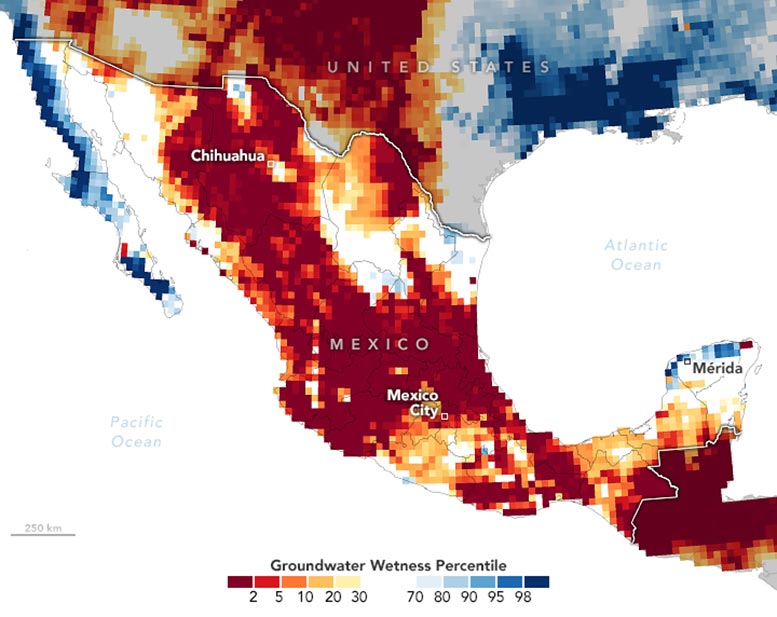

The map above shows shallow groundwater storage in Mexico for the week of May 27, 2024, as measured by GRACE-FO (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment Follow-On) satellites. Colors depict the wetness percentile, a measure of how the levels of groundwater compare to long-term records for May. Blue areas have more abundant water than usual, and orange and red areas have less. The darkest reds represent dry conditions that should occur only 2 percent of the time (about once every 50 years).

Seasonal rains typically begin to fall around Mexico City in June and continue through September, so precipitation may bring some relief to parched reservoirs in the coming weeks.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Michala Garrison, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and GRACE data from the National Drought Mitigation Center.