From Scota to the Saxons: How the Countries of Britain Got Their Names

We live on an archipelago of confusing labels. Are we British? English? Citizens of the UK? And why does a person from Wales call their country Cymru while the rest of the world calls it Wales?

The names of our islands and nations are not just labels; they are fossils of invasion, ego, and mythology. They tell the story of Roman tax collectors, Anglo-Saxon settlers, and a homesick King who wanted to feel bigger than he was.

Dig a little deeper, and you find legends of Egyptian princesses and Trojan giants that our ancestors believed were the absolute truth.

Here is the story of how the countries of Britain actually got their names.

Great Britain: The Painted People and the King’s Ego

First, let’s tackle the big one. Why is it “Great” Britain? Is it a boast?

Historically, the name derives from the Roman Britannia. But the Romans didn’t pull that name out of thin air; they likely adapted it from the Greek explorer Pytheas, who visited in the 4th century BC.

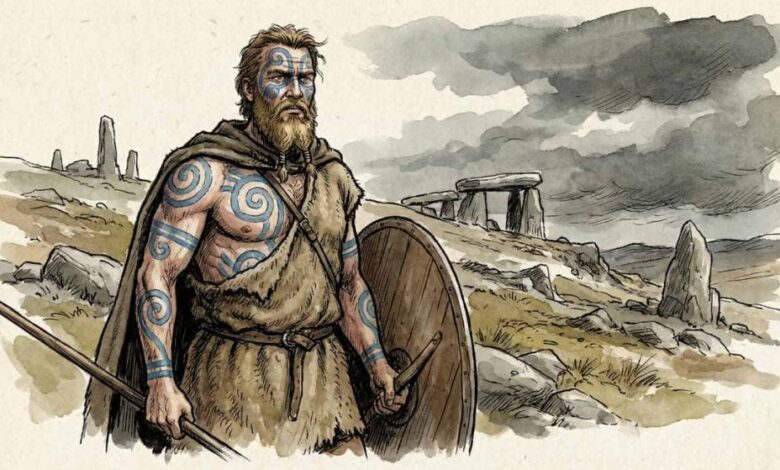

He referred to the islands as the Prettanikē, likely derived from the Celtic word Pretani, meaning “The Painted Ones” or “The Tattooed People.”

So, originally, we were just the Islands of the Tattooed People.

The “Great” part is a mix of geography and politics.

Geography: It distinguishes the island from “Little Britain”—which is Brittany (Bretagne) in France. When Anglo-Saxons fled there, they took their name with them, creating a confusion that required a size distinction: Grande retagne vs Petite Bretagne.

There is also the fact that the British Isles is made up of 4000 to over 6000 islands. There are thousands of islands including the likes of Anglesey, the Farne Islands and so on. But the big landmass, where most people reside, Land’s End to Jon O’Groats, is also known as Great Britain.

Politics: We can blame King James I (VI of Scotland) for making it official. When he succeeded Elizabeth I in 1603, he united the crowns of England and Scotland. Desperate to be seen as the ruler of a single unified island rather than two squabbling kingdoms, he styled himself “King of Great Britain,” forcing the term into the political lexicon.

England: Why Not “Saxon-land”?

The Anglo-Saxons arrived in the 5th century, a mix of tribes including Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. The Saxons were arguably the more dominant political force (giving us Wessex, Sussex, Essex, and Middlesex).

So why do we speak English in England (Angle-land) rather than Saxon in Saxon-land?

It is one of history’s great branding exercises. The church seems to have preferred the term Angli, perhaps because Pope Gregory I famously made a pun upon seeing fair-haired Angle slaves in Rome: “Non Angli, sed angeli” (“Not Angles, but angels”).

By the time King Alfred the Great (a Saxon) united the people, he adopted the title “King of the Anglo-Saxons” but the land generally became Englaland.

The Mythical Version: Medieval monks claimed the land was named after Locrine, the eldest son of Brutus of Troy (the mythical founder of Britain). Locrine inherited the southern lands, which he named Loegria—a name that still survives in the Welsh word for England, Lloegr.

Wales: The Foreigners in Their Own Land

The name “Wales” is possibly the most ironic exonym in history.

It comes from the Proto-Germanic word Walhaz, meaning “Romanised Foreigner” or “Stranger.”

When the Anglo-Saxons arrived, they looked at the native Britons—who had lived there for thousands of years—and essentially called them “The Foreigners.”

The Welsh, however, have never called themselves that. The Welsh name for the country is Cymru (pronounced Kum-ree), and the people are Cymry. This descends from the Brittonic combrogi, meaning “Fellow Countrymen” or “Compatriots.”

So, for 1,500 years, the map has shown two opposing viewpoints: the English view (“Land of Strangers”) and the Welsh view (“Land of Compatriots”).

Scotland: The Egyptian Princess

In English, Scotland simply means “Land of the Scoti.” The Scoti were a tribe who sailed across from Ireland (Hibernia) to settle in the west of modern-day Scotland, eventually merging with the native Picts.

But why were they called Scoti? Medieval history provides a spectacular legend. According to the Scotichronicon (1440s), the Scots are named after Scota, the daughter of an Egyptian Pharaoh.

The legend goes that she married a Greek king, Gaythelos, and was exiled from Egypt (possibly during the time of Moses).

After wandering the Mediterranean, her descendants eventually landed in Ireland and then Scotland, bringing with them the Stone of Destiny.

The Gaelic Name: In Scottish Gaelic, the country is Alba. This is likely a much older Celtic term related to Albion, possibly meaning “White Land” (referencing the white peaks or cliffs) or simply “The World.”

Cornwall: The Horn of the Strangers

Cornwall is a linguistic hybrid, stitching together two languages to describe the shape of the land.

Corn: Comes from the Celtic Kernow or Cornovii, meaning “Horn” or “Headland,” describing the peninsula jutting into the Atlantic.

Wall: The same Anglo-Saxon suffix found in Wales (Wealas), meaning “Foreigners.”

So, to the Anglo-Saxons, Cornwall was literally “The Horn of the Foreigners.” To the Cornish speakers, it remains simply Kernow.

Ireland: The Goddess Ériu

The name Ireland is a direct marriage of the divine and the mundane. Éire (the Irish name for the island) comes from Ériu, a powerful sovereignty goddess in Irish mythology.

According to the Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of Invasions), when the Milesians (the ancestors of the modern Irish) arrived, they met three goddess sisters: Banba, Fódla, and Ériu.

Each asked that the island be named after her. Ériu was the one who prophesied their success, and in return, the invaders promised her name would be spoken forever. The English simply added “land” to Ériu, giving us Ireland.

Summary Table: The True Meanings

|

Country 70294_668bb9-ab> |

Name Origin 70294_55ecf1-4a> |

Literal Meaning 70294_58a7be-b7> |

Endonym (Native Name) 70294_2b33f0-33> |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Great Britain 70294_da53fe-c9> |

Roman/Greek (Pretani) 70294_32e900-e1> |

Land of the Painted People (Great = Large) 70294_e91c5f-fb> |

Prydain (Welsh) 70294_99b85d-b7> |

|

England 70294_ee3e78-46> |

Anglo-Saxon (Engla land) 70294_10c47c-a3> |

Land of the Angles 70294_d4abb7-63> |

England 70294_a461a2-2c> |

|

Wales 70294_3caeea-51> |

Germanic (Walhaz) 70294_ccfd73-31> |

Land of Foreigners 70294_6b7149-ea> |

Cymru (Land of Compatriots) 70294_35cbe2-0a> |

|

Scotland 70294_6d9221-96> |

Latin (Scoti) 70294_ef2cc5-7f> |

Land of the Gaels (or Scota’s Land) 70294_69b4f7-45> |

Alba 70294_6bbbd2-fd> |

|

Cornwall 70294_34241e-57> |

Celtic/Saxon Mix 70294_0f4d6d-27> |

Horn of the Foreigners 70294_305e99-4e> |

Kernow 70294_6bdb0b-a8> |

Source link