The poverty trap

PUBLISHED

January 12, 2025

KARACHI:

Poverty impacts millions of people in Pakistan and limits the nation’s economic potential. During the last 10 years, poverty indexes have shown a complicated picture of regional differences, fluctuation in improvement, and ongoing inequality.

The connection between poverty and economic stability presents ongoing difficulties for Pakistani policymakers. The economic trajectory of Pakistan, one of the most populous developing countries in the world, is defined and influenced by its ingrained poverty.

Over the past 10 years, Pakistan’s poverty rate has varied greatly, reflecting the interaction of political unrest, natural calamities, economic policies, and worldwide economic trends. Between 2013 and 2018, there was a steady drop in the number of people living in poverty. Between 2013 and 2018, the national poverty rate decreased from 36.8 per cent to 24.3 per cent, according to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS). Increased economic growth, improved agricultural output, and the implementation of social safety programs were the significant factors behind this improvement.

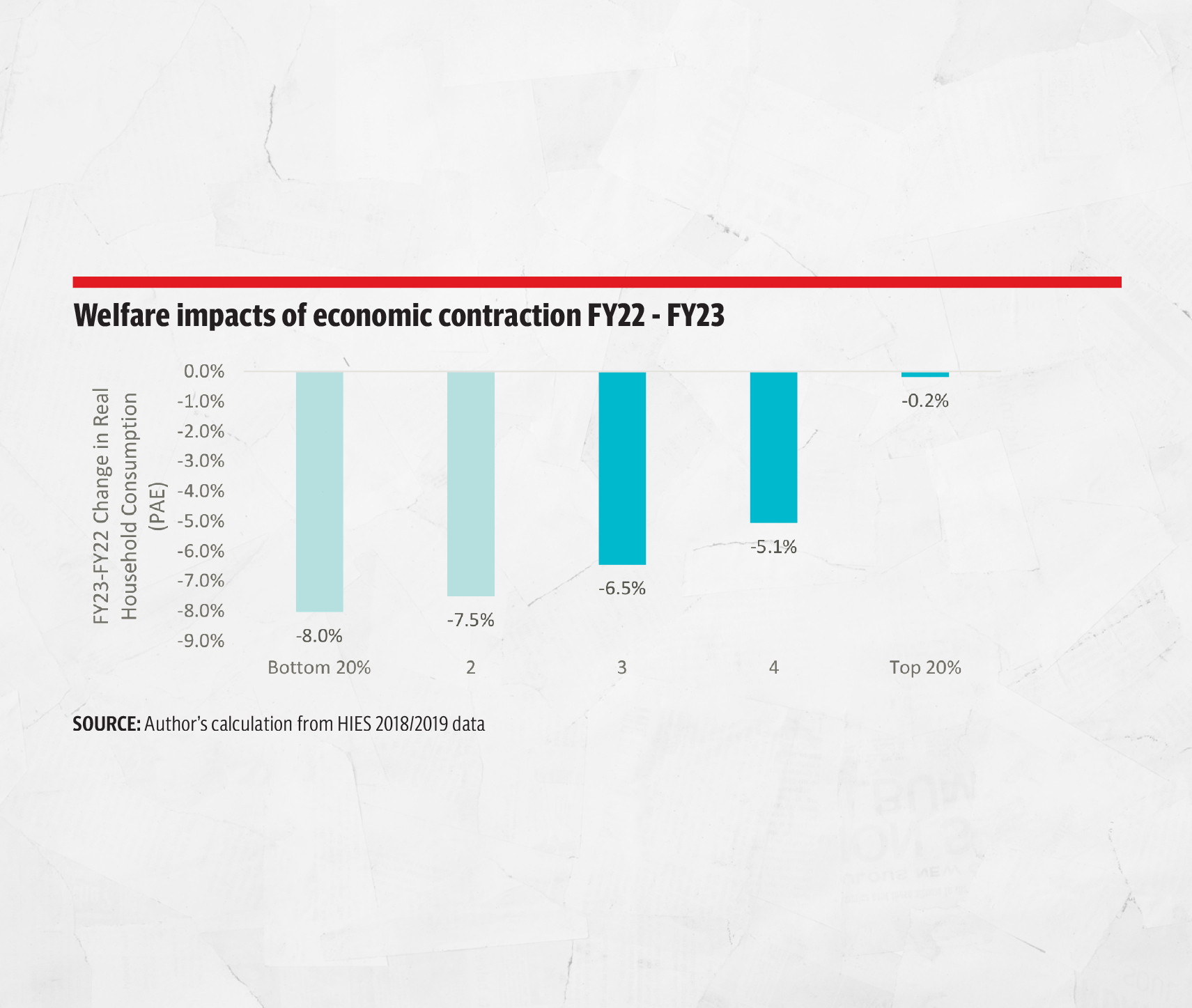

However, much of the progress was undone by the economic recession that followed in 2018, which was made worse by the Covid-19 pandemic. Income gaps grew, unemployment rose, and inflation shot up to double digits. More than 32 per cent of people were estimated to be living below the poverty level by 2023. In 2022, floods further destroyed livelihoods, especially in rural areas, forcing millions of people into poverty.

Due to easier access to services and infrastructure, urban areas typically fared better than rural ones. Compared to Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Sindh and Balochistan saw little development and continued to be hotspots for poverty.

Vicious cycle

Poverty has far-reaching effects on the economy, resulting in a vicious cycle of low productivity, limited development of human capital, and stunted economic progress. “Poverty indexes are variable to measures and can’t define poverty but yes, economic fluctuation directly links to poverty in the country, and there are several ways to control it,” said economist Dr Kaiser Bengali.

Workers in poverty are less productive due to malnutrition and a lack of access to high-quality healthcare. Innovation and industrial output are the need of time. A big chunk of the population has less disposable income due to high poverty levels. Reduced consumer spending affects domestic market demands and impedes economic growth. “We can help reduce poverty by investing and uplifting agricultural reforms in the country, which will be a help in creating more jobs, and also help the country to stabilise in terms of economic growth,” Dr Bengali added.

Public spending on welfare has increased, putting a strain on the government’s finances as it spends more on emergency relief, social safety nets, and subsidies for disadvantaged groups.

Poverty fuels social discontent, political upheaval, and increased crime rates, all of which have discouraged foreign investment and impeded economic growth.

GDP growth and inflation

In the last decade, Pakistan’s GDP growth has lagged behind its regional counterparts, averaging between three and four percent. A low GDP results in less money coming into the government and less money available for development initiatives. Poverty can decrease by roughly 0.5 per cent for every 1 per cent growth in GDP, according to the World Bank. However, this potential influence is limited by Pakistan’s low GDP growth, which prolongs cycles of poverty.

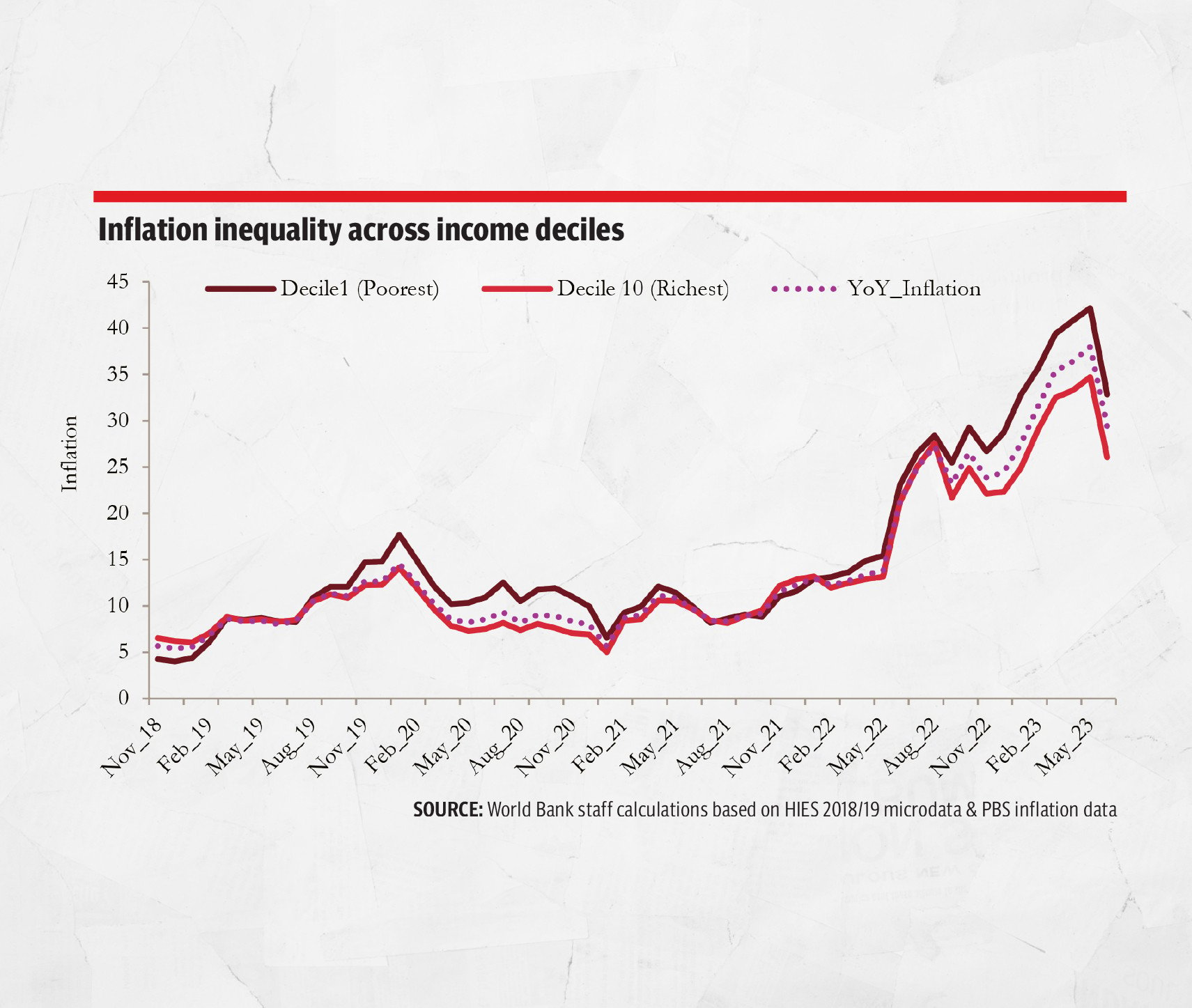

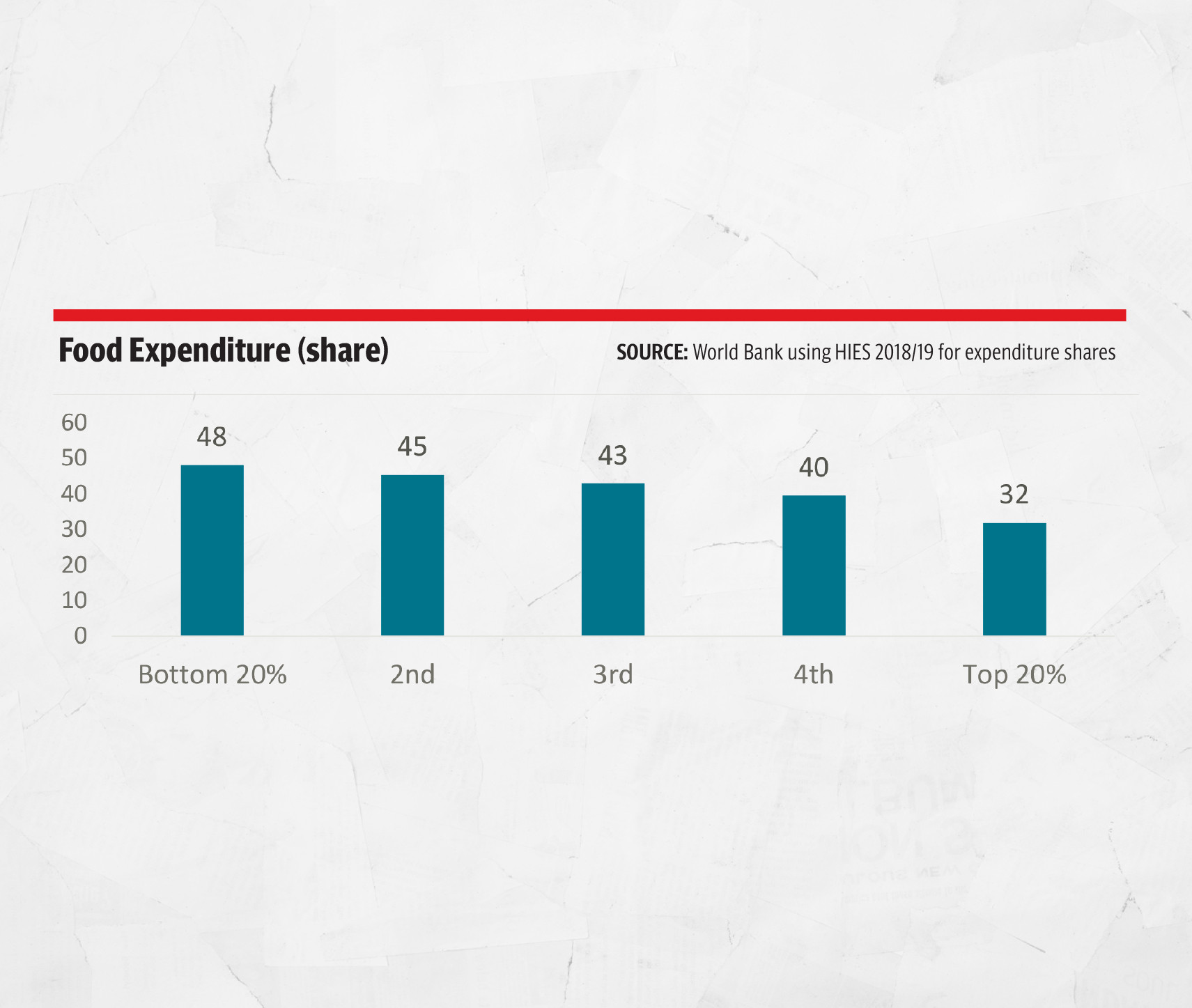

Pakistan’s persistent inflation, which peaked in 2023 at 24.5 per cent, disproportionately affects low-income households. For the impoverished, necessities like food and fuel frequently represent a greater portion of spending. Their purchasing power is diminished by rising costs, which increases food poverty and limits access to services. In recent years, an extra three million people have fallen below the poverty line due to food inflation alone, according to a survey done by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

In Pakistan, income disparity is still glaring. Nearly 27 per cent of the nation’s income is controlled by the top 10 per cent of earners, while less than 4 per cent is available to the poorest 10 per cent. The vast majority of people are left vulnerable by this wealth disparity, which also inhibits economic mobility.

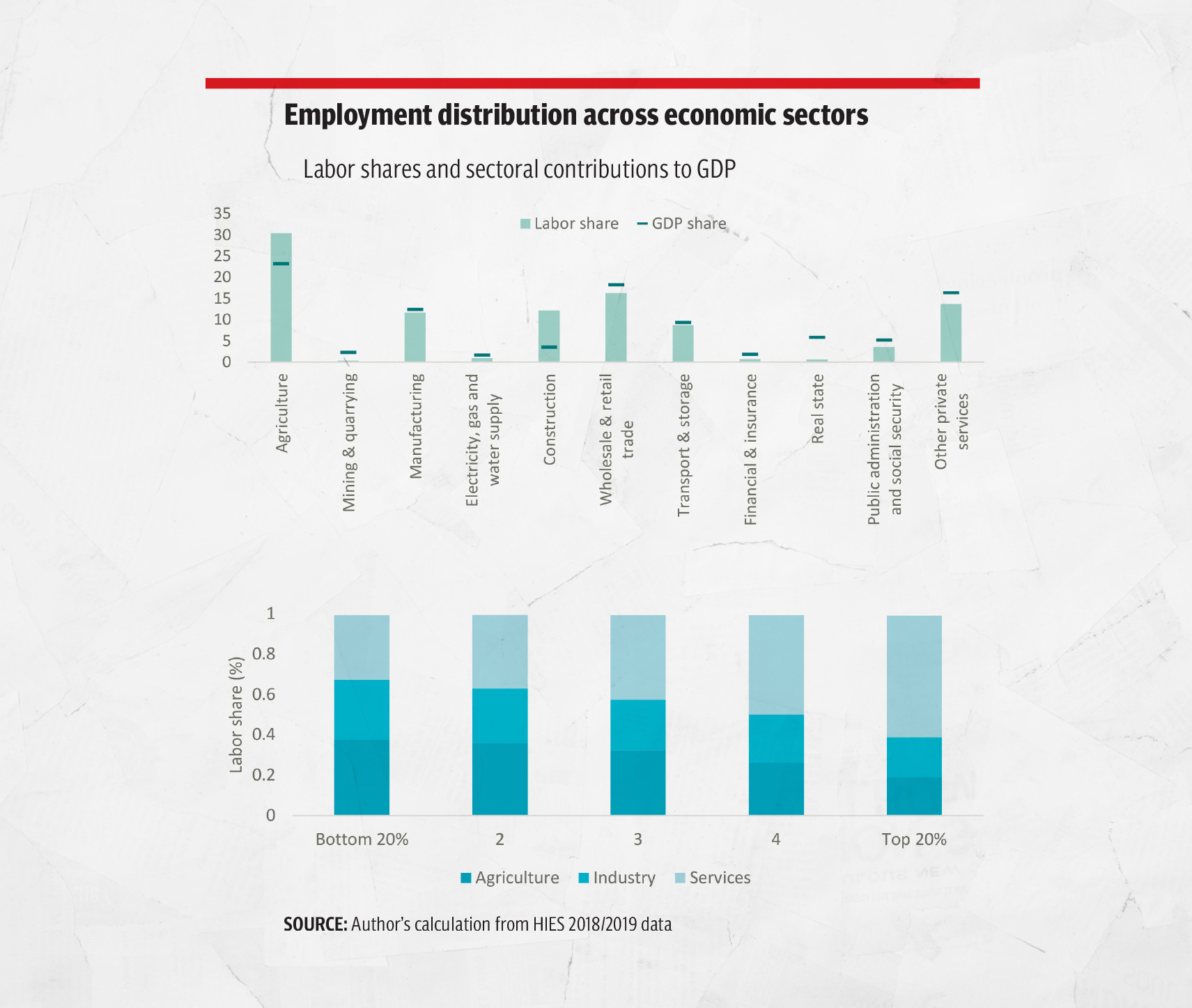

Pakistan’s labour market finds it difficult to accommodate its expanding workforce. For millions of families, economic instability is sustained by high unemployment rates, especially among young people, and pervasive underemployment in the unorganised sector. Agriculture, which is mostly dependent on Pakistan’s economy, is vulnerable to climate change and erratic policy. Economic growth is also constrained by a lack of innovation and limited industrialisation, which inhibits the production of jobs and revenue.

Poverty hinders the development of human capital by limiting access to high-quality healthcare and education. A workforce that is untrained and unwell impedes innovation and production, which slows economic progress. Welfare initiatives frequently require significant funding from the government. Although required, this takes money away from possible expenditures in industrial expansion, infrastructure, and education—all of which are important forces behind economic advancement. Because poverty lowers disposable income, consumer purchasing is curtailed. As a result, the demand for goods and services is reduced, and the expansion of the private sectoris discouraged.

Tackling the challenge

A comprehensive and long-term strategy is needed to end the cycle of poverty and unleash Pakistan’s economic potential. “We need to realise that whatever we have done in the past decade has not worked, which is why we have failed and are at this stage,” said economist Dr Farrukh Saleem.

Economic diversification and job creation, tax incentives, skill development initiatives, and better access to credit are all ways to help small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) that can enhance economic growth. On the larger scale, investments in industries like IT, renewable energy, and textiles can increase exports and generate job opportunities.

Increasing agricultural productivity can be achieved by implementing contemporary farming methods and offering financial assistance for seeds and fertiliser, by connecting farmers to metropolitan centres through improved roads and markets in rural areas.

Other factors include uplifting education by ensuring that all children attend school which can help create a workforce with the necessary skills. By establishing vocational training facilities, young people can get employability-boosting skills that are relevant to the market.

It is essential to address regional imbalances and broaden the reach of cash transfer programs to cover additional recipients. National expansion of affordable healthcare programs is necessary. Decreasing tax evasion and enacting equitable taxation can raise money for initiatives aimed at decreasing poverty. Making microloans more widely available can empower small business owners and encourage financial independence.

Making use of technology, by digitising government services, can reduce corruption, and welfare programs can be delivered effectively. IT skill training programs can provide opportunities for freelance work and remote work, particularly for women.

Floods and droughts can have a less negative economic impact if thorough disaster management plans are developed. Vulnerable populations can be shielded from poverty brought on by climate change by promoting sustainable agricultural and industrial practices.

Learning from mistakes

Although poverty is still a significant problem in Pakistan, it is not something that cannot be controlled. “The problem that we haven’t learned from our mistakes during the last 10 years, is the necessity of political will, focused actions, and consistent policies,” said Dr Saleem.

Pakistan can put itself on track to drastically lower poverty over the next five years by concentrating on social safety nets, education, job creation, and climate resilience.

“We want our economy to grow but poverty increases when GDP goes down and vice versa. GDP growth was 0.9 per cent in the past year while population growth is 2.5 per cent, how will you match that number even?” lamented Dr Saleem, adding that the rule of thumb is nothing that we have done in recent past has worked for us so we need new strategies and planning to help us curb this menace.

World Bank report

If the economy continues to be on the better side, the World Bank predicts that poverty will gradually drop to 18.7 per cent by 2025. This hopeful scenario depends on several variables, such as strong support for industries like agriculture, increased public investment in poverty reduction, and efficient inflation control. But overall it should be kept in mind that recovery may be uneven and brief if fundamental changes are not implemented, such as enhancing the labor market and social reforms for inflation.

Restoring buying power and promoting economic growth depends heavily on keeping inflation under control and maintaining exchange rate stability. Reducing poverty will depend on controlling inflation, particularly in the price of food.

Low-income households can see an increase in their income through investments in labor-intensive industries including manufacturing, agriculture, and small businesses. By generating jobs and raising living standards, these industries have a multiplier impact.

The most vulnerable can have a safety net if programs like BISP are scaled up, their coverage is expanded, and payments are linked to inflation. To reduce welfare losses, these programs’ targeting and efficiency must be improved. Disasters like droughts and floods brought on by climate change are a constant menace. Efforts to reduce poverty can avoid setbacks by investing in resilient infrastructure and bolstering catastrophe risk management.

It is crucial to address regional inequities by implementing focused interventions in areas with high rates of poverty, especially in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. In certain areas, a particular emphasis on infrastructure, healthcare, and education can lessen the gap.

The World Bank report also emphasised on how crucial current poverty data is for guiding policy decisions. However, policymakers are using out-of-date data because Pakistan’s most recent thorough poverty study was carried out in 2019. The report uses a microsimulation method that blends high-frequency macroeconomic indicators with historical household survey data in order to close this gap.

By taking sector growth and household-specific inflation rates into consideration, it emphasises, because of its high labor intensity and contribution to household welfare, agriculture, which employs 32 per cent of Pakistan’s labor force, remains essential in reducing poverty.

The report also points out the differences between urban and rural areas as well as across Pakistan’s provinces. The two states with the greatest rates of poverty in 2023 are Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (31.5 per cent) and Balochistan (45.9 per cent). Despite doing better overall, urban regions had a greater increase in poverty during times of crisis because they relied on industries like manufacturing and services, which saw major contractions.

Due to their reliance on agricultural activities, rural households demonstrated greater resilience despite having higher baseline poverty rates. Their recovery is still shaky, though, since gains are being undermined by inflation and a lack of popular backing.

Source link